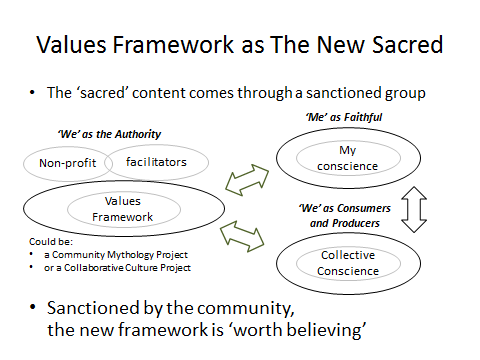

Last year I attempted to run a Community Mythology Project (CMP) in Duvall, WA. The premise was recognizing that myth making is fundamentally a human driven process – that seems obvious right? If it is, we can take control of the process. The Duvall CMP fizzled. Why?

I have a few possible explanations, and a theory for what to try next.

- The community was not interested in thinking too deeply about culture

- Other priorities conflicted

- People didn’t understand it

- Artists were more interested in their personal art that in creating art as a group

- I did a lousy job

- etc., etc.

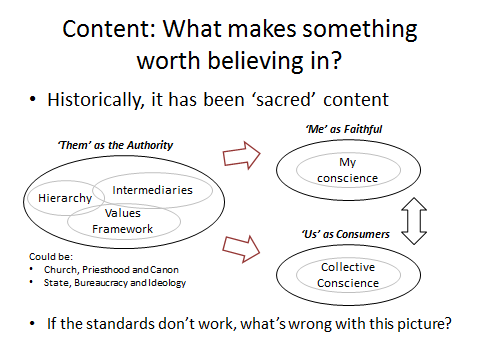

I’m sure all of these, and more, played a role. On factor, however, that I’m fairly certain had a strong role in keeping people away is quite simple: people aren’t used to creating myths for their own consumption. We believe myths come from an authority. Actually, we don’t even think about them as myths. They are our religion, our national ethos, our consumer rights, the media addiction and so on. We also don’t think of ourselves as choosing a myth. Because we need it to be authoritative, we would rather believe it found us. When the time was right, God revealed it to us, we think.

The fact is we had choice. We may have abdicated the decision by accepting what our parents, or neighbors or pastor said. Abdication is still a choice. So we deceive ourselves on many levels. We think our faith is not a myth, we believe we didn’t choose it, and so on. So the biggest paradigm shift is to simply accept this fact: we pick our myths. The next level beyond that is to say we create our myths; but that might be too much for most.

So let’s start with picking our shared story. Where do we go shopping? Is there a local outlet? A myth boutique? Perhaps Amazon has a myth department?

Catering to that consumer mindset might not be a bad first step. If it is too hard for people to make up their own myths, perhaps they can just order one up? How would that work?

- First of all, we need to define the dimensions of their choice.

- Second, we need myth-creatives, the guys and gals who can bring one to life.

- Third, we need a group purchase order – shared story is by definition adopted by a community.

- I was going to add shared locale as a constraint, meaning that people should be close to each other. With the internet and social media, however, that doesn’t seem to be a defining characteristic, even though people will meet up sooner or later.

That’s enough to start with. So let me recap: the first baby step in making community mythology more acceptable is to introduce the myth boutique. Think of it as an agency, a proxy authority that prepares myth for consumption. This introduces a layer of indirection that may be enough for us to make the leap. Someday we may mature to participating, and indeed the boutique system will allow creative to participate, and won’t stop them from consuming their own product. How exactly this work? Let me narrate a little scenario. Let me know how it resonates.

John is 21 and fed up with his parents trying to ram their religion down his throat. It seems archaic to him, and just doesn’t resonate. However, they take it extremely personal and he hates to disillusion them. ‘Why can’t they be more rational?’ he wonders. As much as he loves them, he wishes the topic wouldn’t always come up, and he feels it gets in the way of a truly reciprocal relationship. Why can’t things be more direct and simple? He is also tweaked a bit by the questions of origin and purpose. Where did we come from? Where are we going? What should we strive for in life? Is there a redemptive purpose, or is living for experience all there is? Should he just enjoy his youth, or should he sacrifice his own pleasures for the sake a God or country?

Vexed, he decides to Bing on the Internet to see what other options are out there. He knows about other religions – Buddhism, Judaism, Mormonism, etc. However, these seem just as archaic and outdated as the stolid belief system of his parents. New Age stuff seems a bit out there, with irrational believers who use pop science to justify all kinds of stories. The worst part is they actually believe in galactic alignments dictating Earth history, astrology and messages from aliens in crop circles. That’s too far out for him. He’s a rational man.

He thinks he might as well make one up! For grins, he types ‘how to create a mythology’ into the Search input and hits enter. Many results come up, including references to books about mythology, personal myth counselors, psychologists and, to his surprise, a link to a myth creation wizard. What strikes him about the description is that it is both rational and creative. The language resonates with him – it assumes that the myth making process is human process, which is what he has always known in his heart.

Elated, he goes to the site, which explains a number of things, including the background, assumptions and choices. As a consumer, he really likes the idea of imputing some parameters and getting a relevant mythology as an output. The best part about it is that the mythology comes with a community of like-minded people. ‘Genial!’ he exclaims, catching himself. He’s alone in his room. But the walls just ‘fell off’. Suddenly he feels like the universe just opened up, and the moon and stars are within his grasp.

Eager to get started, he begins with the profile. A guided set of questions help him identify with a worldview tendency. It makes him think about his assumptions, and then his values. In the end, he gets a summary, which he doesn’t like, not because it’s inaccurate, but because it shows a side of him he’s not too content with. He’s delighted he can see what other options there are, and then aligns with a set of values he wants to have.

After completing the Value Profile, he goes into an aesthetic profile – he selects movies and music he likes, picks from various images and statements until the system presents him another summary, this time of his aesthetic direction. He validates that as well, also tweaking it towards the direction he would like to go. He does have a conscience after all, and if he’s going to have a hand in creating his own belief system, he applies high standards.

After a few more quick profiling questions, including social preferences (he’s more of an introvert that thrives with small groups), he’s finally done. The whole process took about an hour of concentrated effort, and he feels like the system has a good handle on what he wants. All that is needed is the myth and corresponding community. This is where his expectations get realigned – not so fast!

It turns out he’s part of a longer running process, and while there are others who are potential cohorts in his myth community, it turns out the myth has not been created yet. This is actually not a bad thing, since he now has the chance to influence its development. He’s strongly encouraged to participate in the validation process, which is systematic and straight forward. He is also asked to pick a sponsorship level. Creating myths costs money, of course. There are creative people, editors and publishers to pay. Since this is more exciting than church, he signs up as a Sponsor and pays his dues.

Once there is critical mass for the myth creation to start (there are enough participants and sponsors), the myth requirements and timeline are published. John monitors progress as writers and artists respond to the call. They get their creative brief which includes the values and aesthetic direction, and they start work. Over a three month process, they go through brainstorming sessions, establish a myth framework (which has been put to a vote to the sponsors), go through a creative process to write the story arch, characters and embellish them artistically. This involves poets, playrights, dancers, photographers, painters and many more who mostly volunteer their time out of passion for the process. They get some compensation, and sponsors have the option of rewarding stellar output.

Once the myth reaches a critical mass, the community site is launched and everyone receives a brief in email so they can study up on the story. A big kickoff event brings everyone together. Participants meet in person and online, including the artists, to participate in a rich presentation that includes poetry, performance and art exhibitions. The goal is complete immersion. This is not unlike a Star Trek or Star Wars convention, except in this case, the consumers were directing the content, and the individual artists were free to express themselves as they saw fit, based on the creative brief. There is some creative direction, but it is not coercive; the artists are encouraged to express themselves in their own artistic voice. This brings out a plethora of interpretations around a shared story, which is a crucial practice in community-driven mythology. It teaches people to think for themselves, fosters tolerance and a richer artistic experience for all.

John is delighted with his new found ‘religion.’ It pre-occupies his mind in a good way, he has community, feels a sense of purpose and collaboration. After a while he is willingly consumed by the new ‘cult’. In the back of his mind he knows it’s partly his own concoction. He relaxes about that and plays along because his imagination has been ignited with creative meaning. His soul is in play with creative imagination, and it satisfies the non-rational side, which he now recognizes. Because he knows he had a level of control in its inception, he believes in it in a healthy way. He’s not deceiving himself into thinking it was handed down by God. The community validation and the fact that it agrees with his own conscience makes it even more cogent than the ‘revealed’ religions in his mind. He uses the shared story and rich artistic artifacts surrounding it to deeply internalize the values and lessons, and this guides his behavior. Finally, he thinks, he has a ‘religion’ he can believe in, and live out its values in his daily life.

Is this the scenario we have to build to get Community Mythology to take off? Let me know your thoughts. Also, contact me if you’d like to help implement this story!

— Roy Zuniga

Ballard, WA

——

Copyright Roy Zuniga 2012 – all rights reserved