Disclaimer: what follows is a human-authored myth. Any association with science is unintentional. Although this story may contain insights that are true for you, the author makes no claim to universal or exclusive Truth. Side effects of reading this may include cognitive dissonance.

We long to be connected to something out there that can’t be pinned to a location. Sure we try, for example by talking about ‘the ascension to heaven’, etc. The more we think about that, the more nonsensical it becomes. Where exactly is this platform in the sky?

On earth, we strive to attain a sense of place, of where we are. We compare our physical self with people, places and things around us; we increase or diminish our sense of importance and worth through correlations. The comparison game is what we do, and depending on how we visualize the prescient void, we can either build ourselves up, or tear ourselves and each other down. We sense we can influence the comparison, and so influence the outcome. We feel lifted up when we believe we’re doing well in the comparison, that we’re ‘doing what we’re supposed to’. We feel depressed and worthless when we fail God.

Moreover, how we succeed or fail in our earthly comparisons impacts our spiritual comparison. If a parent always put you down, you will feel put down by God. On the other hand, if you were the apple of Daddy’s eye, you will be succeeding with God. Thus the belief we bring, makes the difference. To succeed with God, therefore, you must change your comparative belief.

We can’t really compare ourselves with our spiritual source, which is not any of the things around us. Yet because we’ve been programmed for comparison as finite agents in this culture, we can’t help but to compare ourselves with that distinctive spiritual something ‘out there’. How to get a handle on it? How do we really interact with it in a meaningful way?

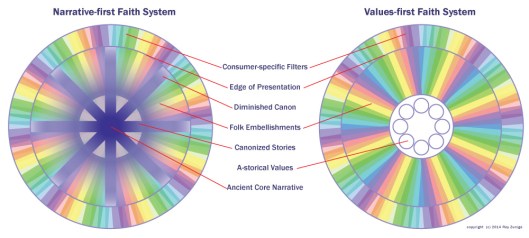

To make the comparisons with this other presence, we need real images, so we make up representations of aspects God via prophets, saints and mythological creatures. Myth-making goes hand in hand with the intent of our beliefs. We attain a system of spiritual comparison that leverages perceptible icons, imaginable heroes and villains to anchor our comparisons, according to the belief we bring. The approval or disapproval of parental figures in our youth to a large extent determines how we believe. That’s why religions spread geographically, passed on over generations. If you’re not satisfied with what you inherited, how do you change your beliefs to attain a positive comparison with God? It takes a lot of mental and spiritual discipline. Do this you will be changing the game you grew up with and hopefully find a better center for your being and a good life. Many do in fact onboard to another religion. We must realize that this whole religious game is there just so we can get up in the morning with a sense of purpose.

The thirst for meaning and the fact that there is a comparison game going on clues us into the fact that there is something else going on. We must become aware of the mechanisms of perception for this ‘other’ presence. We are receivers and transmitters, and we don’t sense how the information flows though us. How do our prayers get to the other side? We know we are connected, but we don’t see any wires, so to speak, or perceive the transmissions themselves. This is because it happens at a level of being we can’t perceive directly. It’s like looking a leaves waving from a distance. We assume there is a wind even if we’re not feeling it directly. This flow to the other can only be described by metaphor.

Let’s give this ‘other plane’ a name. I’ll call it ‘Uranthom’. We’ll also call the traditional comparison game we play on earth ‘malgod’. I want to replace malgod as my primary mode of obtaining meaning and importance. We may have to make up more names for other concepts later. To keep it simple, this will do for now. Uranthom is the place, and malgod the game. Both will be defined as we explore the ideas here.

Let’s think Uranthom as a plane of existence devoid of time. Our interaction with it can be thought of in terms of spiritual transmissions. Keep in mind, this is only simile and not accurate from an engineering perspective. Instead of meaning by comparison with others on earth, let’s look at meaning by quality of the experience transmitted to Uranthom. We could combine the comparison games by sharing the quality of experiences with others. However, we’ll keep the two games apart for now, and assume that the Uranthom transmissions are for their own sake. Others may be involved, but the goal is not to have them validate you by comparing each other’s experiences.

What exactly is being done with these experiences on Uranthom is not something we have any firsthand knowledge of. Perhaps we are the eyes and ears of God, and since he’s bored being Other, he built in a connection with creatures so that He could know everything that happens through us. Uranthom could be a massive accumulation of information that God uses for his own assessments. After all, how do you know you are all-knowing? We can explore the Uranthom mythology at another time. For now, let’s concern ourselves with the phenomenology of the transmissions.

Since we are concerned with meaning, not every transmission to Uranthom is the same. Some matter more than others. I appreciate excellence. Others may have a different intuition. Experiences necessarily involve other people, places and things. We can consider them transactional in the sense that one thing interacts with another and there’s an exchange of some kind. You can’t really have a meaningful experience without interchange, which is foundational to our sense of existence.

In this life, we can choose to engage or not. Other things and people will either respond to your action, or poke your inaction. In either case, there is action/reaction and these are experienced by both parties in the transaction. The meaning of the transaction is subject to interpretation, as there is no true ‘fact of the matter’, there is only perception of the importance which is imputed by the actors and the spectators around who happen to be watching and who are also impacted by that same transaction.

Actors transact with other actors, who in turn push others, and on the game goes on, as we all bounce around existence like kayakers in a stream. We can apply our will through the paddles, for example, and influence where whether we park our kayak in a safe eddy to rest, or drive head on into the whitewater. We have that choice, and either is important based on the interpretation you give it.

Whether you are a watcher or an action maniac doesn’t matter. What matters is the meaning you impute to it. You may work in a corporation and be ‘winning’ by not being the CEO, or alternatively only ‘win’ by becoming the CEO. It is up to you. Of course, if you can’t become the CEO due to lack of qualifications, then that’s not a game you want to play. We all adjust the games we participate in, but not all adjust it in a way they can win. Many will adjust the game, but not enough, and so they are always losing.

Finding a romantic partner in life is a similar game. Those who are in a lifelong marriage have adjusted to their partner. Those who value freedom may orbit around another, but never quite fuse their lives. Both can be happy. Miserable is the one who wants a lifelong partner and picks a partner who only wants to orbit. She may bend the rules of the game to accommodate, but if she doesn’t change her own game fundamentally, she will be miserable in the unfulfilled co-dependency.

Defining your game means selecting the people you interact with so you can have successful transactions. Transactions with the wrong people may be collisions and ultimately both parties will learn. So both defining the game and picking who to interact with can have a huge impact on your sense of importance and place in the world. Getting in a zone where both the game and the transaction partners are in harmony means you have found peace in life.

In a way, conceiving the metaphysical Uranthom, the metaphorical ‘plane of the other’, is an example of a transactional relationship. Lack of transactions is lack of meaning, and not all transactions are meaningful. Sitting without interactions can be quite miserable (unless you’re a meditative monk), and so we disturb the peace by interacting with others. We get to decide what is notable. For example, as an artist delighted with artistic excellence, high quality paintings are meaningful to me. Great art, as I’ve written elsewhere, is art that connects you with a perceived personality. For you, on the other hand, it might be meaningful to jump off a high mountain in a squirrel suit, drive the fastest cars, complete a round trip to the North Pole or sign at Carnegie Hall.

I want to eliminate the sense of linear progress that is required by the malgod game, where continual improvement is required, and riches can be amassed. Richness to me is an aesthetic moment. Achievement is not imputed to a lifetime; it is likewise a moment. A great achievement in a career does not define you for life. Neither does a failure. There is no need for forgiveness; we may learn from failure or pay the penalty for our actions. Once the transaction has played out, you are the tabula rasa, the blank canvass on which to paint your next great experience. This is a project-oriented existence where you define success, and it can change from project to project.

Uranthom has no time, and it is not finite in any sense. We can only talk about Uranthom in metaphor, so we’ll think of it as a plane. Notable experiences appear as blips of varying sizes on this surface, and the size of the blip corresponds to how notable the experience is, and each of us gets to define what notable is. Prayer and heartfelt affirmations of experiences are our way of identifying what we consider notable.

Uranthom is not cyclical either, since the notion that all things originate from nothing and dissolve back to nothing is nonsensical to me. Such a view makes existence a meaningless game, and any sense of purpose, progress or success is perceptual only, i.e. it has no objective meaning other than being an example of an archetypical behavior in the mind of God. No, everything we think is notable appears in Uranthom. We project importance to the ‘timeless’ event.

Since there is no time in Uranthom, we don’t even have to use words like ‘timeless’ and ‘eternal’. By definition, what we chose to project to Uranthom abides and becomes the core of our soul that we can interact with during our lifetime. It only follows that we can access these notable experience ‘blips’ on the plane of Uranthom at any point in our life. You can access lessons you have not yet experienced because the plane of Uranthom has them all simultaneously. Even now, if you chose to receive all your experiences, you can, including ones you’ll project in the future.

Note that even horrific experiences can be projected and received, so that we may be forewarned and avoid certain types of situations. Note that the reception is devoid of details. I can’t see great paintings I will make because those exist in time. However, I can tap into the emotions and evocations of my notable transactions. There is no need for death to do that. Thus without projecting experiences, spiritual life is dull. We must experience and project and we will develop a drive for more.

Learning from both the negative and positive experiences evolves our consciousness. The collection of these is our consciousness. In our lifetime, we can share our notable experiences with others so they can perhaps evolve their own consciousness. Thus we have collective improvement as humanity.

Uranthom is not finite in any sense we would understand. It can receive transmissions indefinitely, as far as we are concerned. Everyone can transmit. Moreover, what is meaningful to one person in a human-to-human transaction may not be meaningful to the other. I’m not interested in creating another rule set-based religion.

The myth of Uranthom provides principles that help me focus on the quality of aesthetic creations and the transactions that influence their creation. I can get into a zone when creating without regard to time, and this experience has deep meaning because I can project the best onto the plane of Uranthom. I also don’t have to worry about a career progression, or the feeling of inadequacy that not having an artistic trajectory brings with it in the traditional model. You are insulated from the insulting eyes of those who might judge you.

The plane of Uranthom also provides a framework for change, as we can adopt new goals for meaningful experiences and likewise cast those on the plane of Uranthom. It provides a framework for recasting your life from time to time, which is essential not only in our various life stages, but also in times where world-view shifts are required for us to keep the possibility of differentiated experiences on a healthy planet earth.

— Roy Zuniga

Kirkland

Copyright (c) 2016 roy zuniga