When we deliberately express intent we are functioning as ‘mind’ for the Universe, which then reacts as ‘muscle’ to produce the desired effect. This is metaphorical, of course. How an individual’s expression of intent causes a response in our world is a mystery. We don’t have language for it. We need a myth to drive home the point, but that’s beyond the scope of this particular post. So let’s try a mundane analogy.

If I wake up on a Sunday and decide to go for a run, my body activates in anticipation without me needing to think about how to give explicit instructions to each muscle. My legs are restless, itching to move, like a dog ready for a walk (your actual experience may vary). Which is different than when I decide to lay in bed watching a morning show.

I’ve found the universe responds to my intent. I won’t get into specific cases here because each can be argued by those looking for a polemic, and it would derail the point intended here, namely, that your worldview shapes what you can wish for.

As we articulate intent, there is a mysterious orchestration that considers other intentions being expressed in our world, and where possible, an alignment is made that enables as many of them to be fulfilled as possible. Yes, it is an ecosystem of intent/fulfillment, and yes, it is amoral in the sense that two contradictory intents can be fulfilled at the same time. Once satisfied, we are personally thankful and move on to the next intent. And so the cycle goes: my ‘mind’ — our collective ‘mind’ — and the ‘muscle’ of the Universe working together. This is a matter of faith: you either believe it or you don’t. Not much you can scientifically prove in these assertions.

Rather than defend them, I’d like to focus on how intent itself is formed. Where does it come from? Why do I spend my energy forming certain intents and not others? Why is it that I can’t desire certain things or behaviors even if rationally I recognize them as laudable, perhaps for someone else. For example, why do so many of us know deep in our hearts that we live an unsustainable consumer lifestyle, but can’t seem to get into the groove of a minimalistic sustainment lifestyle? Why, on the other hand, are third world villagers happy with so little? Many don’t form any intent around the Western consumer lifestyle. Why is that? Isn’t it obvious, we think as Americans, that if you can accumulate stuff, you should? Demand drives supply, and that creates jobs.

I articulate certain intentions because I believe they are the right ones. I have conviction about them. But what does it mean to know what you want? Obviously, you know what you want, and when you want it. You can even rationalize why in terms that fit in your world view. But why is that particular desire there in you, or even in a whole segment of society, so that your desire is normal. But do you really know how that all got there, and what the root cause is that allowed your mind to even conceive of that intent as a desirable outcome?

Let’s assume that intent is essentially a life force that all creatures have. There’s a lot of controversy around the nature of will, and frankly, it’s not something that can be proven one way or the other. Philosophers have recognized intent as a ‘will to life’ (Schoppenhauer), or a ‘will to power’ (Nietsche). Whether it is inherent to us, or ‘the thing in itself’ outside of us (Kant), I’ll leave as a mystery for now. Here I want to focus on the boundaries put on the expression of intent by our worldviews, by the sacred stories we accept and how they frame how we think. If the nature of intent is in the eyes of the philosopher, we can look at behaviors. What is the structure of the expression?

Rainwater flows according to the contours of the landscape. It doesn’t accumulate on hill tops, but rather finds its way through valleys and ravines into rivers and ponds, pulled by gravity. The topology of a landscape dictates likely areas for water to pool.

Think of your worldview as the topology of your mind. Desires flow within predefined channels. Depending on the contours, desires can only accumulate in certain ‘pools’ of intent. For example, if we believe in the progress of history and a heavenly kingdom, we can’t really express intent for reincarnation. On the other hand, if freedom means lack of desire for material comfort, your desires will be for happiness only in the ascetic life. Industrial progress is meaningless, to be loathed.

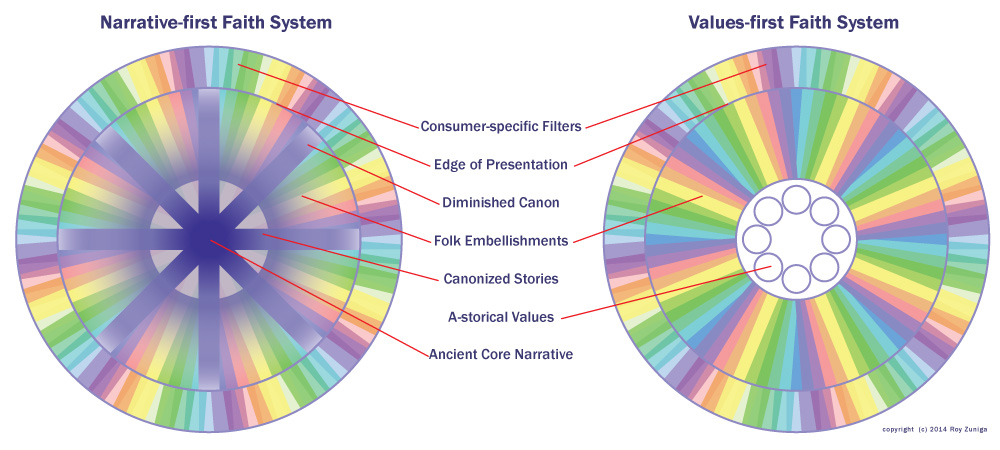

We can recognize that the formation of specific intents is a function of the mind. To formulate intent, we think in terms of outcomes. Something formed my mind so that desires get channeled in only certain ways. The formative forces molding the topology of our mind are the myths we hold sacred. We’ve become accustomed to thinking about myths as written texts of great import, like the Iliad, Vedic literature, the Talmud, the New Testament, the Koran, etc. In reality, sacred stories evolve and vary as much as language does. Think of all the languages and dialects in the world — that gives you a rough idea of how many myth and myth variations there are. The less codified they are into a holy book like the Bible, the more they vary by region and need.

As Joseph Campbell has pointed out, Myth allows us to talk about topics that language otherwise can’t handle, like the Afterlife. Without creation stories, we could not formulate meta concepts about life after death. Do we go to heaven to be with Jesus, or reincarnate repeatedly until we achieve Nirvana? Sacred stories constrain how believers can think about the answers. Sacred myths open us up to categories of thought and practice we otherwise would not have.

As a young man, a paradigm shift happened when I adopted a new sacred story about God and humanity. I ran across a few Evangelicals who gave me categories of thought for the Holy Spirit, which I then exercised to great effect. I will never forget this spiritual experience. I had been evangelizing and preaching in Northern Ireland, converting people, and we went to a house church in the evening. Believers there were very Charismatic, which means that they believed in the ‘gifts of the Holy Spirit’, and spoke in tongues. They praised God without inhibition and I got so caught up in the euphoria that I felt a rush of freshness pour through me like a waterfall. It was the Spirit of God flowing through me! I was elated and stunned at discovering a dimension of my humanity that I didn’t know existed. The Charismatic worldview allowed for this experience. Without the worldview shift, I would not have formulated such intent, nor experienced the shift in the experience of reality.

If I had bumped into Budhists or some other religion instead of the Evangelicals, and was open to their message, I’d be exercising my spiritual faculties within a different framework and therefore different experiences. In other words, the texts and traditions we adopt as sacred provide us with a framework within which we can exercise our spiritual faculties. It provides a topology for the flow of spiritual intent, and hence the manifestations that can arise from those expressions. The same can be said about the expression of any intent. It is bounded by the channels in our worldview.

To illustrate the point, let’s compare hypothetical expressions of intent based on three philosopher’s worldviews:

- A. Schopenhauer: If we think the cycle of will deterministically results in Craving → Fulfillment → Boredom that leads to a pessimistic despair to be escaped only via asceticism, i.e. the renunciation of cravings, then the believer will channel all intent towards one of those ends.

- F. Nietzsche: If we believe that personal passionate choice in the service of master morality is the right application of intent, then we’ll work towards the prosperity of those who strive to be ubermensch, and marginalize the existence of a slave class with their despicable slave morality.

- S. Kierkegaard: Or we can simply accept Christianity with Jesus as the reference point as he lives in the pages of the Bible, and express our intent as opposition to a lame and self-serving Christendom.

In these examples, the worldview bounds the possibilities of individual intent. Worldviews are shaped by the metanarratives, the collection of stories and myths we hold sacred. The framework of the story we adopt creates the channels for possible action in our mind, deepened by an emotional connection which is the function of empathy for the characters in the myth.

Thus we can affirm that the ‘topology’ shaped in our mind is deterministic of the types of intent that can be expressed. Therefore, great weight and importance must be placed on the sacred narratives. They are our future. We shouldn’t be victims to them, but rather their God, so to speak. We must learn to author them.

The Moses of this world, the Joseph Smiths, the Buddhas and the Mohammeds who invent or otherwise articulate religious worldviews end up creating the channels through which millions will funnel their desires and actions, conceiving and articulating intents that get orchestrated by the Universe into our day-to-day reality. Nietzsche understood this dynamic and created his own sacred text in ‘Thus Spake Zarathustra’ to help channel how his followers thought about things like eternal recurrence. Our reality is literally shaped by the myth makers.

Thus the creators of the sacred myths wield immense ‘control’ over the future of humanity. Frankly, people can’t live without the stories they hold sacred. How we evolved to be this way is a good question that frankly may never be answered. Some say we are hard-wired for language. Perhaps we are hard-wired for myth as well. In any case, this is how we articulate intent. If we passively accept worldviews that preempt certain necessary outcomes, then we seal our own doom. We have a moral obligation to take control of the myth-making process to preclude unsustainable behaviors, and predispose those that are.

This is easier said than done. We all know that people groups with sustainable behaviors can’t defend themselves against the onslaught of militarized consumerism. Nor do we necessarily want to bring back old myths we find archaic and even insulting to science. The evangelical experience also teaches us that blanket conversion of entire populations is unrealistic. Whatever the answer is, we have to try knowing that myth-authoring and dissemination plays a central role.

— Roy Zuniga

August 2020

Duvall, WA